Equity, Equality and School Redistricting

The False Narrative that Equity Demands Redistricting

I’ve noticed that corporate diversity-related programs that used to be (some still are) called “Diversity, Equality and Inclusion” have been increasingly been renamed with the newer phrase “Diversity, Equity and Inclusion.” That begs the question, what is the difference between equality and equity and why are we seeing this change?

According to Howard County Public School System (HCPSS) superintendent Martirano, “If I distributed the same level of instruction to every student … it’s a detriment to all students in a nonequity-based approach,” Martirano said. “If you just do equal, we all suffer.”

Although there is no basis for the statement that all students actually suffer from equal treatment, I think most would agree that the school system should provide disadvantaged, struggling, or special-needs students with extra assistance, as needed. This includes tutoring, mentoring, technology, meals, and, I would argue, even daycare services. In this context, equity is about attempting to provide better outcomes for those who need more help, regardless of the reason why they need extra help. The objective of a public education is to actually deliver an education to all children, not to deliver acceptable average test scores across an entire school or county.

So, when equity is cited in the context of redistricting, it implies that all other student support efforts have proven inadequate, and suggests that the only remaining option is to take the extra step of removing them from their own community school or, conversely, of compelling other students to move into their school. Equity in redistricting is an open-ended approach to the redistribution of students among schools without any measures of success (or failure) that could be applied to determine if the policy is even working. Redistricting is little more than the acceptance of failure.

HCPSS Policy 6010, School Attendance Areas, “establishes school attendance areas to provide quality, equitable educational opportunities to all students and to balance the capacity utilization of all schools.” The policy implies that equity cannot be delivered in every school without a careful allocation of students to schools based on something other than where they live. The policy includes the following distinction between equity and equality:

“Equitable – Just or fair; different from equal in that equality connotes equal treatment, which may be insufficient for equitable access and outcomes.”

In other words, equal treatment of students is no longer considered good policy, even with regard to redistricting. Some believe that a more diverse racial or ethnic school population makes for a better educational experience, which may be true, but may not. It may even help some but hurt others. Evidence suggests that the socio-economic status of parents and their cultural values are far more powerful determinants of educational success than anything else. Moving kids to a new school does not fix the disadvantages of a poor family or one that does not encourage educational performance.

Coleman Hughes, in What the New Integrationists Fail to See, discusses this call for school “desegregation” as the solution to performance disparities:

“A liberal consensus has settled on the view that American schools must be more thoroughly integrated before black and Hispanic students can perform at the level of their white peers.… If Americans have clustered along racial lines for the past five decades, free from state coercion, then why do neo-integrationists perceive a problem? … inequality was not an inherent consequence of racial separation itself. Rather, the inferior performance of black schools was the result of other factors—most black schools received fewer resources, black families were locked out of many sectors of the economy, black parents were less likely to be educated, and so on. Had all these contingent factors been different, there’s no reason to assume that black schools would have underperformed solely because there were no whites around. Separate was not inherently unequal. It was contingently unequal.”

Redistricting advocates conflate the desirability of racially, ethnically, or socio-economically balanced schools with the question of whether or not students should be compelled to move to a school outside their neighborhood. Not even discussed is how to measure whether such balancing by race or ethnicity even leads to equitable outcomes for those who are lagging, assuming that equity refers to improvements in individual, not average, student performance. Statistics showing the racial and ethnic breakdown of students by school are not evidence of success, nor do average test scores indicate whether disadvantaged students are benefiting. What are the measures of success other than platitudes about “desegregation” as a measure of equity?

Socio-economic factors do lead to neighborhoods with different racial makeups. Less intrusive means are available to increase neighborhood diversity, such as the creation of low-income or subsidized housing, but there will never be perfect representation in every community as long as people have the free will to choose where they live. When political leaders fail to provide for affordable housing, those same leaders often advocate more intrusive compulsory redistricting, which is almost always seen as harmful to the interests of the residents of a community. Even low-income students prefer to attend their community schools with their neighbors and friends.

We have been led to believe that “segregation” is caused by systemic racism, which is also the alleged cause of lower performance for minority children. This assumption leads to the conclusion that “desegregation” and anti-racism to dismantle “white privilege” is the only remaining viable solution.

Coleman Hughes, in A Better Anti-Racism, addresses the problem with claims about systemic racism:

“race-consciousness misdiagnoses the problems facing our society and therefore prescribes the wrong cures…. A movement that defines any racially disparate outcome as white supremacy will inevitably tend toward policies that seek to erase such disparities by fiat—individual rights be damned. If, for instance, the fact that Asian-Americans are vastly over-represented in New York City’s elite high schools (which admit students on the basis of a single test) comes to be seen as a racist outcome, then Asian-American applicants may be discriminated against to eliminate that disparity. The rights of individual students not to suffer discrimination on account of their race will be ignored for what is perceived to be the greater good.”

According to the World Health Organization, “Equity is the absence of avoidable or remediable differences among groups of people, whether those groups are defined socially, economically, demographically, or geographically.”

Equality is about ensuring that every individual has an equal opportunity to make the most of their lives and talents. The result of that opportunity will rarely be equal outcome, as there will be winners and losers. Some may have an initial advantage or disadvantage, or may simply work harder or smarter or benefit from the luck of being in the right place at the right time and making the best of an opportunity.

But according to the George Washington University Milken Institute School of Public Health, social systems have “been intentionally designed to reward specific demographics for so long that the system’s outcomes may appear unintentional but are actually rooted discriminatory practices and beliefs.” This is the “systemic racism” narrative that is being promoted by many racial justice advocates. The equitable solution, they claim, “allocates the exact resources that each person needs to access the fruit, leading to positive outcomes for both individuals.”

This line of thinking parallels the Marxist slogan that resources should be allocated “from each according to his ability to each according to his needs,” which is theoretically made possible by the abundance of resources that a communist system should allegedly be capable of producing. The Marxist economic ideology has been conclusively proven false, as communist nations have impoverished their societies while free market economies have generated great, although unequal, wealth for their citizens.

The problem with the Marxist line of thinking is largely one of human motivation. As Adam Smith clearly discussed in his 1776 treatise, The Wealth of Nations, the individual human need to fulfill self-interest results in societal benefit in what he calls the "invisible hand" of the market. This does, however, lead to inequality, so the question is how can we ameliorate inequality without punishing some and destroying individual incentives?

Research by the Harvard Business Review shows that corporate diversity, including different genders, races, and nationalities, leads to more accurate thinking, better decision-making skills, and greater and faster innovation. But often neglected, and just as important, is the concept of ideological diversity, which is being crushed in educational institutions, and socio-economic class diversity, which is neglected or conflated with racial diversity. A study by the University of Virginia Darden School of Business found that “People who transition between classes can learn to relate to people in a more skilled way, and they are incredibly helpful in groups, as they can understand people from all walks of life.”

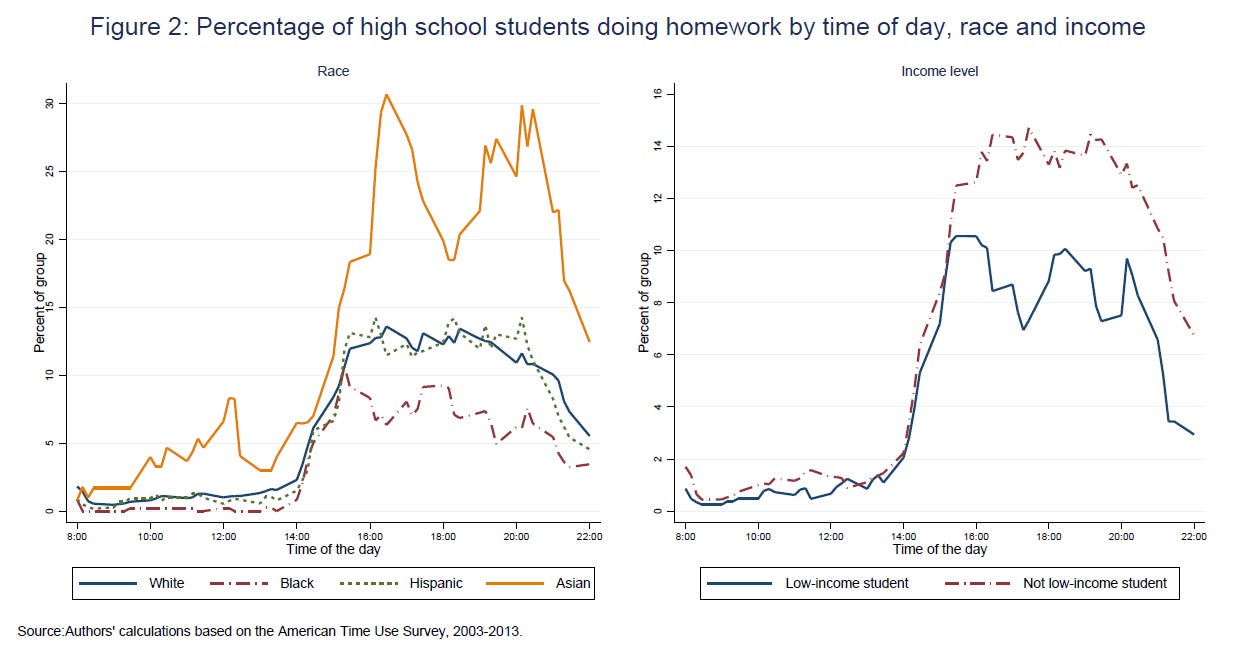

Although nobody wants to talk about cultural differences between groups, culture does affect performance. According to Nielsen data, “blacks with comparable incomes to whites spent 17 percent less on education, and 32 percent more (an extra $2300 per year in 2005 dollars) on ‘visible goods’—defined as cars, jewelry, and clothes.” Furthermore, “black students still spend less time on homework than their white peers … and two out of every three black kids are still living in single-parent homes.”

If performance discrepancies are blamed on systemic racism rather than other proven factors, and “white norms” of education are vilified, our solutions will be wrong and ineffective. If we really want equity, it cannot be based on false assumptions. It must address difficult yet uncomfortable facts. To define and treat people based only by their race or the color of their skin is pure and simple racism, yet this is exactly what we are currently getting in the name of diversity, equity and inclusion.

Can you send a link to subscribe to this blog for shares?